Scientists take AI to Antarctica to examine ancient life

One of the world’s newest technologies is heading to the coldest laboratory on Earth to help scientists examine traces of ancient ecosystems buried for centuries beneath Antarctica’s ice sheets.

The goal? To learn how stable the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is in a warming world.

Dr Georgia Grant and Dr Martin Tetard, both of Earth Sciences New Zealand, will spend seven weeks of their summer camped on the ice as part of the SWAIS2C (Sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to 2°C of warming) science team. ANZIC supports the project through AuScope’s Opportunity Funds.

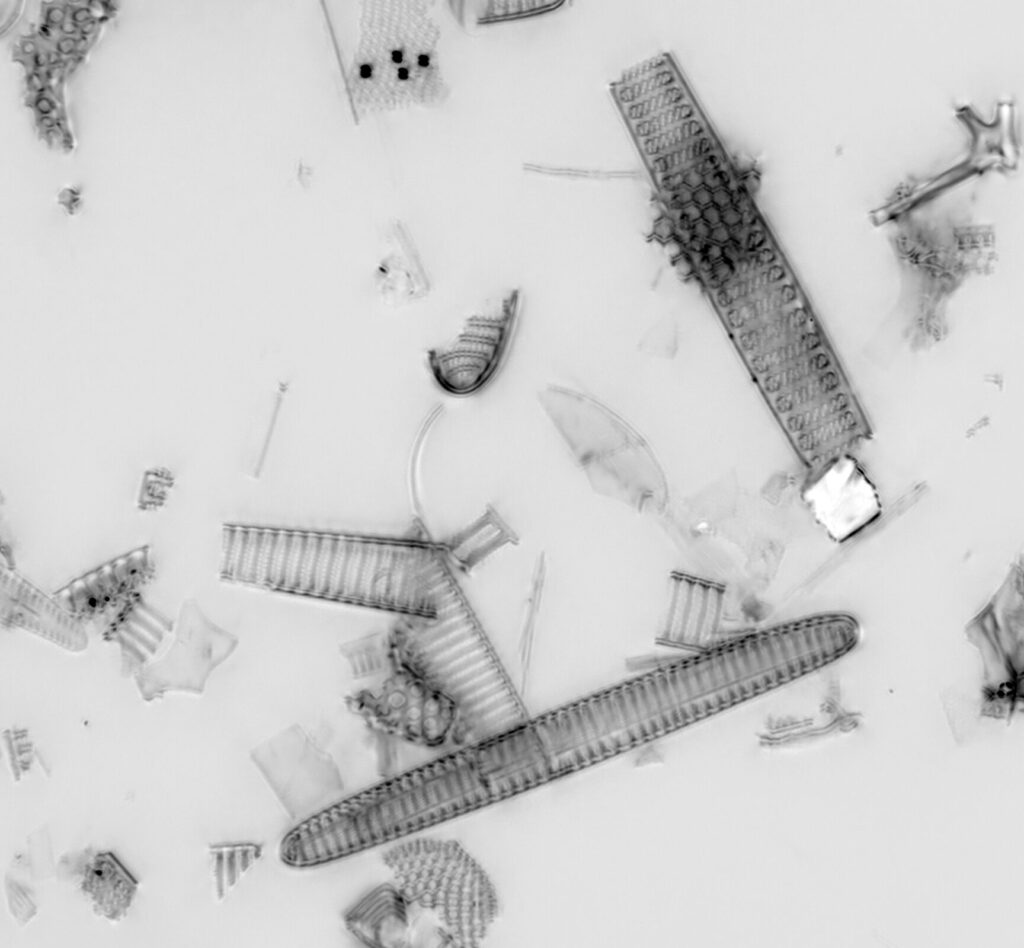

Martin has spent years training machine learning algorithms to recognise microfossils common in the Southern Ocean and Antarctica – the often beautiful, glass-like skeletons of microscopic diatoms, radiolaria and foraminifera.

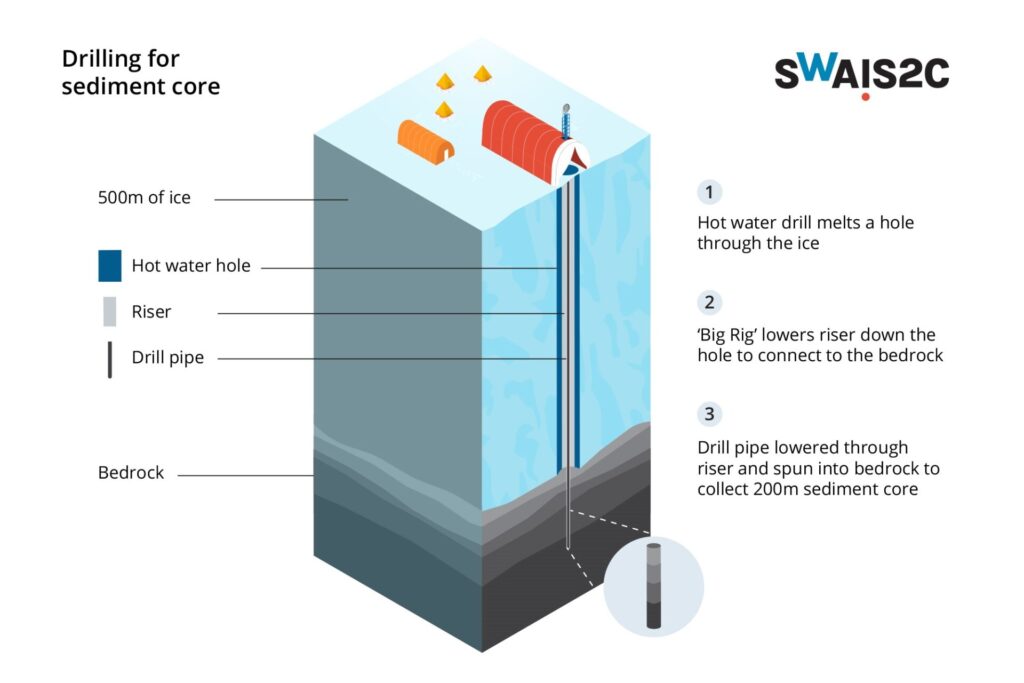

With the help of AI, he will look for these in sediment samples that the team hopes to drill from deep beneath ice. The stacked sediment layers represent chronological samples deposited on the seafloor, stretching back hundreds of thousands of years.

“There are many different species, each with their own signature structure,” Martin explains. “I have trained the image recognition system to tell which is which – and even how healthy they look.”

“Different species thrive in different environmental conditions – some like it colder, others live in warmer waters; some live under ice sheets, others only in open water. By studying which species appear in each layer – at each point in time – we can learn what the climate was like and how the ice sheet responded.”

Understanding the past will help predict the future behaviour of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. This is critical. The Ice Sheet holds enough water to raise global sea level by 4-5 m if it melts completely.

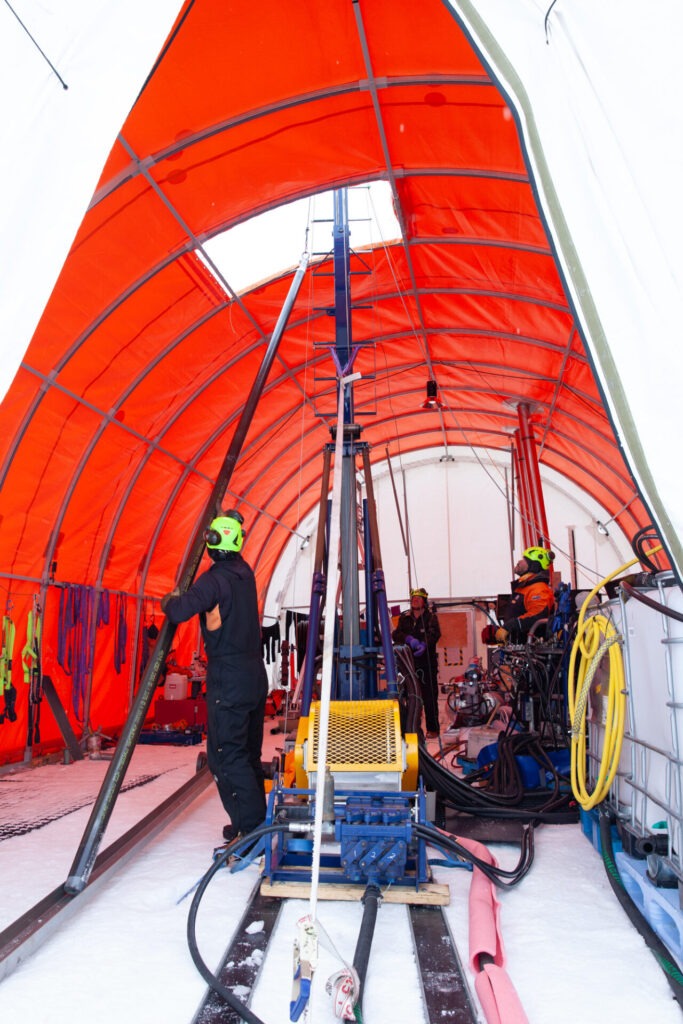

However, getting these precious samples won’t be easy. This is the third Antarctic season for the SWAIS2C project, with previous attempts ending in heart-breaking technical setbacks that halted drilling.

“We are drilling at a new site this year, on Crary Ice Rise,” says Georgia, who will be the lead sedimentologist on the ice. “I’m very excited about getting core, but also very aware of the challenges. “

“At the Crary site, the ice sheet is resting directly on the seafloor – there’s no ocean cavity. This is a first for us. It’s new. It’s untried.”

“It’s a thrill to be part of something so challenging and important.”

The team will use hot-water drilling to melt a narrow drill path through around 600m of ice shelf before employing a traditional drill-rig to retrieve sediment cores from the seabed below. The drill rig has been modified for a better chance at success.

“If the drilling goes well, my job will be to describe and log the core. We’ll be the first of many to look up a potentially million-year history of the Ross Ice Shelf,” says Georgia with an obvious sense of responsibility. “The cores need to be carefully managed and curated so scientists for years to come can study them with confidence.”

Even simple details, like knowing which way up a core is oriented, can be tricky to monitor – but is critical to get right.

“There are some tricks!” confides Georgia. “Like using different coloured rubber bands to mark the top and bottom of each core comes up from the drill hole.”

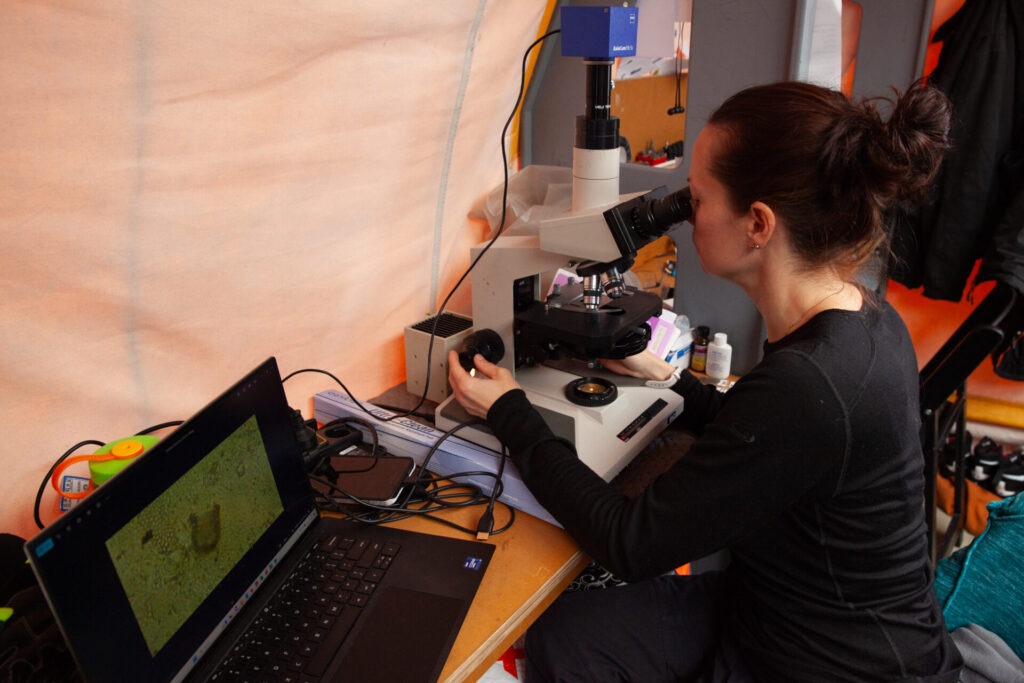

After Georgia has marked, described and cut the cores into one metre sections, they’ll be passed to Martin, working in a small lab housed in a container on the ice. . There, he’ll prepare microscope slides from samples of different core layers and set the AI system to work on the huge task of cataloguing and counting the microfossils.

“There are hundreds of species, across different periods of time, so scientists tend to specialise in just one group or period. Instead of needing dozens of experts, the algorithm has learnt from them all.”

“Recognising and manually counting each microfossil is long and painstaking work. AI makes this much, much faster. We get nearly instant results, instead of having to wait until after the expedition to do that work.”

“We can then share the data with experts around the world for them to interpret.”

“Going to Antarctica is a secret dream of mine,” says Martin. “I’m very happy to be testing this technology and camera that I’ve developed in these extreme conditions.”

Georgia is also well prepared for the adventure.

“My time on the drilling ship JOIDES Resolution on IODP Expedition 400 and previous drilling experience were really important training for my role this summer in Antarctica,” says Georgia.

“I see it as a pastoral role, really,” she adds, “taking care of the core.”

It’s a role Georgia extends to her colleagues, too.

“It’s important to me that the camp is a great place to be, that we work well as a team. This is a remarkable opportunity to draw on the diverse skills of an international team working toward the shared goal of understand the stability of this ice sheet. Ultimately, it is a question that will affect us all.”